Worse Than The Warrior Part - 1

by Mark Montgomery

Margaret could not tell if it was blood or cow piss that splashed her face. She tried but could not stop shaking. Her nearly five year old ears were deafened by the gunshots from the Kalashnikov. Next to her, distressed village cows bellowed in violent pandemonium. She heard nothing. Panic propelled her close to involuntary defecation. The cows had already breached that threshold. Ten pubescent girls lay dead in front of her. Their blood flowed in rivulets down the embankment. The earth was too hard from the Karamajong sunshine to absorb their final fluid.

“You!” The tall warrior smacked Margaret about the head. She stumbled. She did not look at her grazed knee. Sweat glistened on the intruder’s naked torso. He raised his rifle. Margaret wet herself – but she did not cry.

“Start marching!” Margaret regained her footing. She still could not hear, but she could smell. She smelt the fresh cow pats of the terrified herd. She smelt the eddies of dust that they kicked up in their distress. She smelt cordite from spent ammunition. She smelt the fresh blood of the ten young women who lay dead at her feet. Akello, Achiro and Arach lay motionless. They would never play with her again.

She followed the direction of the pointed weapon. Four other almost 5 year olds had already been marshalled, barefoot, into single file. She knew them all.

A Karamajong settlement

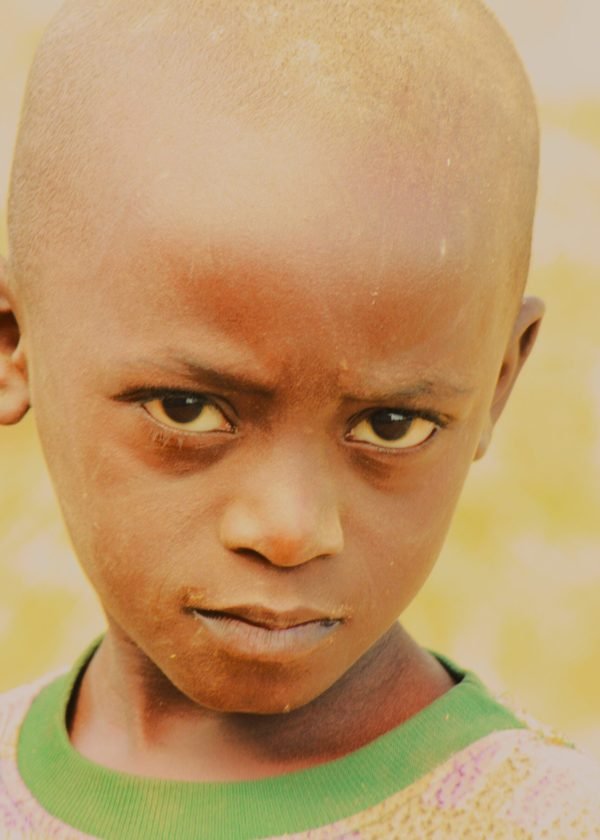

Karamajong boy with traditional scarification

Barely half an hour ago they were helping each other balance yellow, plastic, jerry cans, on their heads for the daily 4 kilometre expedition to the well.

The threat of invasion by Karamajong warriors was ever present, especially since their village had 96 cows. In Karamoja, the arid expanse of savannah and bush on the north eastern edge of Uganda, this bovine treasure was as valuable as 96 bars of gold, but more coveted. As long as she could remember, the threat of a lighting attack by the nomadic Karamajong warriors was whispered around the fire, late at night. A sighting here, a rumour there. A confirmed attack in a nearby village. The adults spoke in furtive tones when they thought the little ones were asleep. When the attack did come, it was as sudden but more violent than anyone could have expected. One minute the rural settlement was busying itself with the tedium of the day. The next, a cohort of tree-tall warriors rampaged from one hut to the next. The few men who sat around in the sun, watching the women work, were dispatched with dispassionate alacrity. Before long the screams of ravished women could be heard.

Margaret and her playmates stood planted next to their collection of yellow jerry cans. The spectacle unfolded before them. Then, without warning, they were part of it. Two warriors herded them to the end of the settlement, near the makeshift paddock, where the precious cows were penned. Ten older girls had already been forced into a line. They stood shoulder to shoulder, some weeping, some hurling abuse at their captors. Some were bleeding from their violent and unwanted passage into womanhood.

“What do you want to do with them?” said a warrior, whose nose had obviously been broken in some previous skirmish.

“These 5 little ones…we will take them with us.” The leader was an older man. His face and torso were decorated with several rows of carefully inflicted scars. They ran in several rows down his chest and around his face, like colourless tattoos.

“And these?” The broken-nosed warrior pointed to the ten adolescent women.

“They are too much trouble. If one of them escapes they could tell the army where we are!”

Shoot Them!

“Shoot them?”

“Yes. Shoot them.”

“Keep up!” Again, a warrior slapped her about the head. His tattoo-scars were less elaborate than the leader’s and he wore a collar of brightly coloured beads. They walked straight into the bush. There was no trail, yet the warriors knew exactly which direction to take. They split into two groups. The trailing contingent drove the stolen cattle ahead of them. The lead group raced through the parched African landscape with the children. Three Karamajong warriors kept the 5 children in tow. Margaret was last in line. Their feet began to hurt. The girls were used to walking great distances. The twice daily trek to the well built stamina. The route to the well, although they were barefoot, the trail was well trod. This track was not. The warriors took ways that had not been walked before.

A trail well trod

The razor-sharp twigs from a forest of bone-dry scrub clawed at the girls. The rough terrain slashed at their feet. Just when her hearing returned Margaret could not tell. She thought she could hear a faint sound of an engine in the distance. She put it down to imagination. Then the warrior with the broken nose shouted to the man at the head of the procession. Margaret knew it was a real sound! It was not her imagination! It was a heavy vehicle! Roaring closer! It could only be…

“The army!” whispered little Betty, who was closest to her in the line.

“It is the army!” shouted the warrior with the broken nose.

“Yes!” roared the group leader! “Disperse! We will come back for the cows.” The warriors disappeared into the bush as effortlessly as they had entered the village. Moments later two military jeeps from the Ugandan People’s Defence Force roared to a halt where the girls huddled together.

“Which way did they go!” a soldier shouted.

“That way!” The five children each pointed in a different direction.

“It is no use. We will never catch them” said a soldier with two bars on his olive-green epaulettes.

“You are right. They know this terrain far better than we do” agreed a soldier, as he got out of the second jeep. An army truck pulled up to the group. Twenty soldiers jumped off the high-sided vehicle. The men lit cigarettes. Margaret stood amazed at the lack of urgency. No one spoke to them. They were intent on smoking their cigarettes. She looked at her travelling companions. Miriam was whimpering as usual. “What can you expect! She has only just turned 4” Margaret thought to herself. She did not cry. Smoke break done, the men talked amongst themselves.

A karamajong woman gathering grass

The conflict in Karamoja

“…take them back…” Margaret picked the whispers from the men.

“…well…” she couldn’t hear the rest of what they said. A soldier separated himself from the smoker’s club. He had three stripes on his shoulder. He was shorter than the other men but he did not appear small because of his broad shoulders and his muscular frame. The midday sun flashed off his shaven head as he walked towards the girls.

“Get on the truck” he said to the children. They obeyed happily. They were free! They had been rescued from the warriors! The soldiers lifted the puny children onto the back of the gargantuan military vehicle. They bounced about on the hard, wooden, benches as the truck forged its way across the uneven topography at speed. One of the soldiers seemed to be staring at her. Margaret looked away. The African landscaped flashed by. The sun grew lower in the sky. Margaret could not recognise a single thing that she had noticed during the kidnap trek with the warriors. She looked behind her. Perhaps … no, she still could not recognise a single landmark. She looked back at the soldier staring at her. There was a strange look in his eyes. Margaret knew they were not going home.

Terego, a Village in Arua District – Northern Uganda

“You will look after her.” The soldier said to his mother.

“Yes, my son. Who is she?”

“She is a child.”

“I can see that, my son. Where are her parents?”

“That is not your business. You will look after her. I will return when she is ready.”

“Ready for what, my son?” The soldier glared at his mother. She looked away. “Will you bring money…food…clothes for her?” she asked hesitantly. He turned on his heel and slammed the door shut as he left the house. The soldier’s mother looked at Margaret, not sure what to say next. She opened her mouth to say something. The door burst open. The soldier was back. His face was contorted in fury.

“…and she must not attend school! Do you understand?” He screamed at his mother.

“…but why…? She is still little….”

“Because I do not want her to!” he cut her short. “If she learns to read and write she will be able to ask questions…”

“Is that not a good thing?”

“No! She will be able to ask about her village. She will ask for directions! Then she will return to look for her parents!” The old woman opened her mouth to speak. “She must not go to school! Do you understand!”

“I’m sorry” The old woman shrugged and forced a half smile. She gave Margaret a pat on the head.

“He has a gun” she sighed.

Terego, the Village in Arua District – Northern Uganda, 6 years later.

There was no engagement party. There was no wedding. The soldier walked into his mother’s house smelling of drink. The redness of his eyes testified that he had been smoking njaga1. He was in a foul mood as usual.

“I will take her now!” His words were slurred but carried unmistakable resolve.

Karamajong child of the streets of Kampala

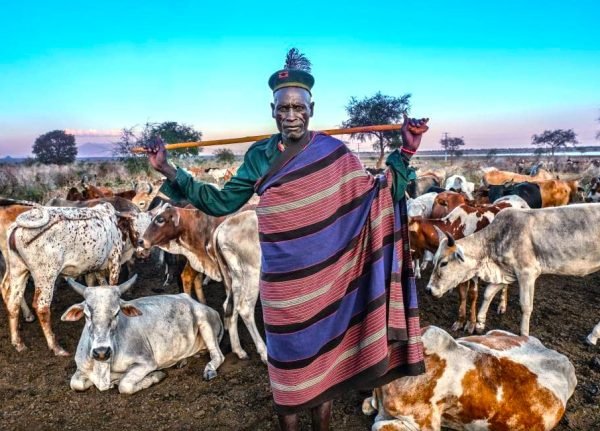

A Karamajong cattle hurder

“No! It is too soon” argued the old woman as she drew Margaret to her side. “She has only started developing breasts!. The soldier took three giant strides across the small room and ripped Margaret from the old woman’s grasp.

“I will take her now!” He yanked Margaret by the arm with a violence that sent his mother crashing to the ground. The door slammed behind them. He half carried, half dragged, the screaming 11-year old Margaret to his shack, at the other end of the village. Before she reached her new home Margaret knew the truth. He rescued her when she was kidnapped from her village – but he was worse than the warriors.

Over the six years he had come back to check on her at random intervals. Invariably, he was of a vile disposition. Invariably, he beat her with ferocious violence, for no discernable motive. Fear was constant. She lived in uninterrupted anxiety – never knowing when he would walk through the door. He never brought food. He never brought money. He never brought clothes. He brought pain.

Margaret was relieved when he left the shack the next morning to return to the army barracks. She knew not when he would return. She had no illusions. When he did return he would do so empty handed and drunk. He would want food immediately. She had given up trying to please him to mollify his moods. He would beat her severely because he wanted to beat her severely. There was no escape.

Her first born, John Mawa, arrived on Independence Day. Was God being cynical? She had never known freedom. She had never known independence. “Now you send me a first born on Independence day! Who will feed him! Who will clothe him!” Her prison had shrunk.

By Christmas the next year, John Mawa was taking his first steps. Margaret used this event to mark the arrival of Chandiru Natalia. Numbers and years meant nothing to her. She measured the march of her life by the low points and the even lower points along the progress of her days. Five more children were to follow, almost on an annual basis.

“How will I feed them!” The soldier replied with a savage beating. When she regained consciousness she resolved never to ask him for help again. Her anger moved her to action. She worked the plot of ground behind the shack and grew vegetables.

She made mats out of papyrus and sold them on market day. She brewed the local beer and sold that as well. The income provided her growing family with food and clothes, and medical care and soap.

Karamajong child of the streets of Kampala